Chloë, reporting from Rions – part 4

Our very own Chloë Schwartz left on June 25 for a 6 month internship at Château Haut-Rian, in Entre-Deux-Mers. Read the July 19th, August 16th and Sept 16th posts for her full adventure! This is the last part of this series.

“My one-line summary of Harvest is it was August and suddenly it was mid-October and I was tired. If this doesn’t do it for you, here’s the longer version:

One day, Pauline asked me to watch her carefully as she prepared the yeast. We got two buckets of hot water and dumped them into a large tub and added cold water until it was 35-37°C. Next, we added the packets of yeast and stirred them up with our hands, which felt amazing. After we had pumped the yeast into the cuve, Pauline announced that she had to go run some errands and left me to prepare the yeast for the next tank’s fermentation! I was honored but terrified. Fortunately, it went off without a hitch, and, going forward, I prepared a lot of yeast. For white and rosé, the type of yeast used can impart significant flavors on the final wine, but it doesn’t really matter for red. That being said, there are differences between the yeasts, such as the level of alcohol they are able to withstand before dying. The yeasts used for fermentation are all the same species (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), but have brand names ranging from the clinical (“F33”) to the confusing (“Syrah”, because that strain was discovered in the Rhône). For the whites & rosés, yeast was added a couple days after the grapes had been harvested (after the wine had been pumped through a refrigeration unit and débourbage (filtering out the must) had been performed; for the reds, activated yeast was added directly to the pump alongside the freshly arriving grapes.

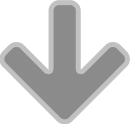

And then it was time for the reds. For the reds, the two presses were wheeled away and replaced with a big scaffold we constructed to hoist the large hose from the pump up and over all of the different tanks. The winery reception for the red grapes was a real pump n dump – the grapes arrived and were pumped directly into the tank. No refrigeration was necessary.

Yeast is poured into the pump with the arriving red grapes / The scaffold used to deliver the red grapes to the tanks.

The contrast between the vinification for the reds and the whites/rosés was stark. Before, there had been myriad choices, with each decision imparting distinct results on the wines’ outcomes. Without their skins, the white/rosé juice was much more sensitive, which increased the pressure and decreased the productivity. The reds were easy by comparison. Whereas we could only fill one 200 hL tank (6-7 bennes), maximum, with whites on one day of harvesting, we could do 2.5 easily on a big day of reds (the record is 15 bennes).

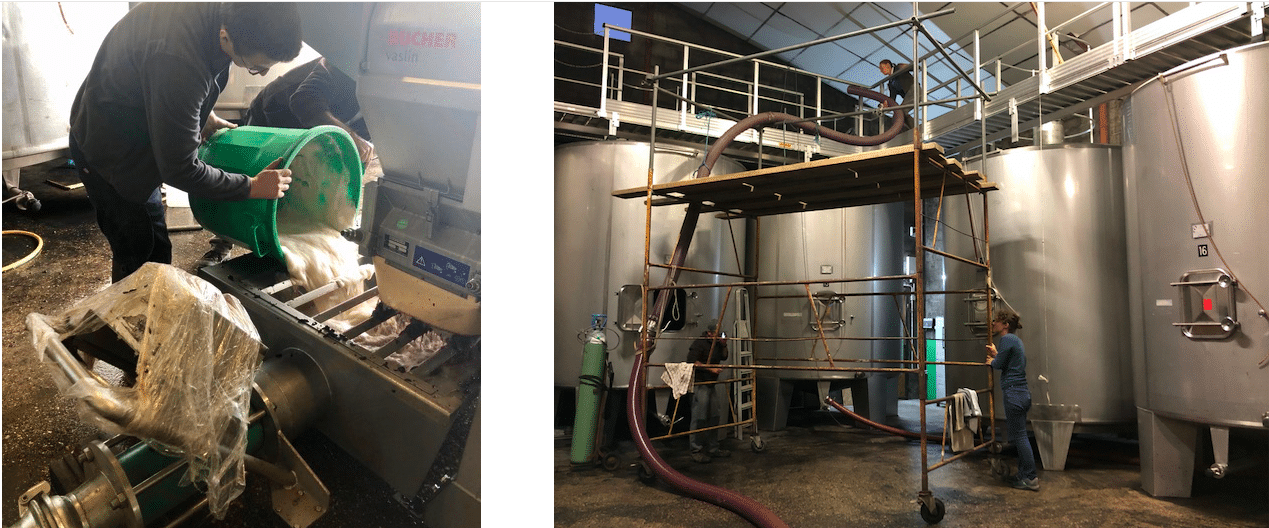

With the reds fermenting, we began remontage and then remontage aéré (once the density had decreased a bit) to extract color and tannins from the skins and to oxygenate the tank. Remontage was a direct pump-over from the bottom to the top of the tank, while remontage aéré involved emptying the tank into an open basin that another hose pumped from over the top of the tank. This is where the faggots came into play: each tank had one faggot installed over one of its lower openings so that grapes would not pass through the hoses. Most of the tanks came equipped with small notches so that the faggots could be attached with wire. In one tank, there were no notches, so we found a large rock to hold the faggot in place. For a couple tanks, the faggots were badly made, so when the grapes passed through they stopped up the hoses. Meanwhile, at the top of the tank, the hose was connected to either what looked like a pie dish with holes punched into it or a device that rotated as liquid was pushed through it. Both did a good job of wetting the cap, but we spent the last 5 minutes of each remontage manually spraying because apparently there is always a spot that does not get covered (which is where mold, acetic acid, and all sorts of other things you don’t want in your tank will develop). Initially, we did remontage on each tank for one hour twice a day, gradually decreasing the time until we were only doing 10 minutes daily. Due to the heat and sun, the grape skins were particularly thick and therefore hard to extract from this year, but Philippe the oenologue was impressed with our color development. Like many tasks I’ve been assigned, I first found remontage incredibly frustrating and, after a couple of days, came to enjoy its rhythm.

As the season shifted into fall, the aroma of roasting peppers and the sound of hunting season filled the air. Everyone loves to complain about the hunters. They wander through vineyards they don’t own and along public running paths, with an air of entitlement as though they’re the only ones who should be occupying this land. Considering that harvest was only halfway over, it seemed particularly foolish to go hunting in vineyards. Pascal showed Géraldine and me this video at 7:30 a.m., while we were doing levage a couple months ago. As we have stood around complaining about the hunters in the past few weeks, it has been frequently imitated.

Once one of the tanks of sémillon was nearing the end of its fermentation, we transferred it to barrels. Now, the added task of twice daily bâtonnage was mixed into the routine. It is quite the upper body workout to scrape the bottom of the barrel and stir up the fine lees and it’s really loud. However, it is a good way to work off all of the harvest croissants! Performing bâtonnage dramatically raises your internal body temperature, which is quite welcome as the days grow chillier and the massive doors to the winery remain open to release the circulating alcoholic fumes. Since we initially filled the tanks, we have already done ouillage (the refilling of tanks) thrice. Ouillage happens most frequently at the beginning – by comparison, with barrels from 2016-2017, I have done ouillage three times over the course of my entire stage. I also had the opportunity to clean some barrels recently, which involved a long metal hose attachment that had a spherical shower head in the middle that sprayed water everywhere.

Everything at the winery was put on pause for one day to harvest the nobly rotting sémillon for sweet wine. It was growing on a beautiful, organic hillside parcel that is too close to the Garonne to be considered Entre-Deux-Mers, but, if made into a sweet wine, can be classified as Cadillac. Despite the stunning views, this was truly one of the most disgusting tasks I have had in my time here. For those who are not rot experts, noble rot looks just like regular rot. The only way to tell if it’s the good kind is to really stick your nose into the bunch and inhale. Reek of vinegar? Toss. Smell like nothing? Keep. But, it’s not that simple, because often a bunch will have an area of bad rot and an area of good. So you need to let your nose really explore the entire bunch and then trim away the bad bits. And there are spores that puff out of the bunches as you squeeze them. And flies swarming around the sugary juice. All of that gets into your nose too. You glance into the buckets of everyone around you and their yields look just as gross as yours. Because we were only harvesting for one day, it was hard to get a good sense of what a prime bunch looked like. The general mantra of the day was “when in doubt, toss it out”, but we were also trying to work efficiently; it’s much slower work than a regular harvest. And the yields are lower: whereas one vine renders one bottle of regular wine on average, one vine of botrytized grapes renders merely a single glass of sweet wine (if that).

Remontage aéré involves emptying the tank into an open basin that another hose pumps from over the top of the tank/ botrytized grapes: differentiating noble rot from regular rot is a delicate operation.

This was not the end of its grossness. When we did debourbage, which we had to use a tractor benne for because we were out of space in the winery, the wine looked like the inside of an infant’s diaper. Unfortunately, bad bunches had been harvested and there was some volatile acid. The following week, when Philippe came to taste, he was in a bad mood and snottily asked if we had machine harvested the sweet wine because he couldn’t understand how manual pickers could have let this happen. Then again, I can’t really imagine Philippe, with his boat shoes, slicked back hair, and paunch accentuated by a sports coat and brightly colored scarf collection picking grapes.

One morning, my landlord, Bernard (a different Bernard), knocked on my door and asked if I wanted to join him in ten minutes to see the mascaret, which is the (tiny) tidal wave that rolls down the Garonne. What I thought would be maybe a couple of hours turned out to be an all-day event with a local association that meets for one day annually to do this walk and see the wave. We started along the river in Verdelais (claim to fame: where Toulouse-Lautrec is buried), walking by fishing shacks, guinguettes (outdoor summer restaurants), and very orderly man-made forests, before climbing uphill to Sainte-Croix-du-Mont, a village built on top of beds of fossilized oysters. In the village, we discussed the association’s finances (everyone’s annual contribution of 5 euros helps immensely) and had an auberge espagnole (a potluck) with a lot of peanuts and bourru. Bourru is semi-fermented wine that old men here love (which explains why so many were always hanging around during harvest). You can buy it at farmers’ markets, but the real objective is to know a winemaker, so you can show up at the winery any time with your empty plastic liter bottle and fill it with the tank that meets your desired level of fermentation. (For the winemaker’s opinion: Pauline was hosting a dinner party one night and a friend of hers brought bourru as a “fun thing” and Pauline was a bit miffed, seeing as she lives next to a building full of bourru.)

After lunch, we walked to a nearby château whose owner did not seem particularly thrilled to host us. He walked us downhill, below his house, into a series of super deep caves built into the oyster walls and lined with very old barrels (they were empty; some had caved in on themselves). The caves are constantly 14ºC and super humid. Graffiti that had been scratched into the gunk along the walls in the 1800s remained perfectly intact. Then we walked back down to the river — 30ish people walking along the side of the road, following Bernard’s cousin who was waving a flag (and had been intermittently lecturing us on local history all day). It felt very dangerous. By the river, we stopped at an old church built on top of a Roman temple and renovated by an adorable retired endocrinologist who enthusiastically told us about the sarcophagi (still containing bones) used to build the church and the sheep that used to live inside of it. After his rapid-fire recounting of a few thousand years of history, he received a round of applause and then we rushed off because the mascaret was not going to wait for us. We all drove to the observation point, which had attracted an impressively large group of people. Unfortunately, it had rained a bit, and the mascaret was nothing special. There were a few surfers and kayakers who had been riding it since Bordeaux, but there wasn’t much left to ride at this point. This didn’t stop more bottles of bourru from being passed around and I found myself in a long conversation with the treasurer of the club, who had made Kosher wine in Bordeaux for 15 years.

At work, twelve hour days began to feel short, but I started falling apart. My shoulder had shooting pains. Both of my elbows started bleeding and didn’t stop for days; same with my index fingers and thumbs. I kept waiting for things to get easier and, well, I’m still waiting. Physical labor in wet, cold weather comes with its own challenges.

Once all the grapes had been picked, we began an intense cleaning process that involved a week of taking every piece of machinery apart, a lot of scrubbing, power-washing everything from the floor to the exteriors of tanks, climbing into crawl spaces that had been filled with rotting grapes and cleaning them out, and soaking everything in NaOH multiple times.

Post-harvest deep cleaning of the equipment / During soutirage, gravity is used to filter out the fine lees.

One respite during this wind-down was daily tastings of each tank. Pauline said that in some years, all of the tanks have tasted almost identical, but that is not the case this year — I have often had to remind myself that I’m tasting components of adjacent parcels that will be mixed together to make one wine. It has been really fascinating to taste the evolution of these tanks; despite fermentation being over, they can really change (both for better and for worse) over a couple of days. Moreover, the conventional tanks taste quite distinct from the organic and sulfur-free tanks. Because fermentation is an inherently reductive process, reduction is a common note among many of the tanks, but usually blows off with some oxidation. The main reason for the daily tastings was to decide when to do décuvage, which is when all of the must is removed from the tanks. Extraction exists on a bell curve; after it peaks in terms of flavor, you should really décuve within the next day or so to avoid astringency and other undesirable flavors.

For décuvage, we pumped the wine into another tank, ventilated the original tank a bit, and then two people entered to clear out the must, which was pressed. Initially, we were so low on space, that we had to use the two tractor bennes, a big tub, and the picking machine to hold wine (we had run out of tanks a couple days before the end of harvest). This whole process takes hours and someone needs to stand guard near the tank in case anyone inside doesn’t feel well (it’s warm + you’re doing very physical labor for an hour + the air in the tank is full of CO2 and ethanol), to stop and start the pump, and to exchange forks for shovels. Pauline did one décuvage, but otherwise it was done entirely by men. I did not complain about the gender inequality!

The guys (or, as they’re known in French, les guys) would step over a pallet placed on top of the pump to get in and out of the tank. During harvest, this pump has a grille placed over it; but for décuvage, there is no grille as the must is too clumpy to pass through it. One night at the local bar, we heard about a nearby winemaker close to retirement who had been doing décuvage that week and fell into his pump and had to have both legs removed.

One afternoon, Pauline invited me to participate with her in the Tour de Cadillac. This is a multi-city tour to raise awareness for Cadillac’s red wine appellation, Cadillac Côtes de Bordeaux. All of the participating winemakers are paired with a local wine bar or cave and then one of the appellation members, who happens to own a vintage cadillac, drives the local journalist Benjamin Bardel, as well as some cinematographers, to each spot. There, Benjamin is met with some bloggers/influencers (who have raced the cadillac on scooters) and interviews the winemaker and the bar/store proprietor while everyone films it. Pauline and I arrived in Bordeaux and wandered down a very empty block to find our assigned bar. As it was her first time doing the Tour, she feared she had been given a bad spot, but it was actually quite nice. We had received a very specific time of 6:37 for when the cadillac would be arriving and, shockingly, it was late. When it did arrive, they parked down the block in front of a car mechanic, who immediately rushed out and wanted to talk about the cadillac with its owner. This conversation lasted longer than the official interviews. Benjamin Bardel is a fast talker who knows his camera angles. After they left, some friends of Pauline’s came and we hung out and poured for customers. An older woman stopped by and said she needed to drop her dog at home but would come back. Within minutes, she had returned and, without being invited to do so, pulled a chair up to our table. She even called out to a couple of her friends who happened to be walking across the street to sit down and join all of us. Subtle looks of surprise were exchanged at our end of the table, but we all chatted amicably and enjoyed the entertainment she provided.

The Tour de Cadillac: local journalist Benjamin Bardel arrives in a vintage Cadillac.

In the long saga of “this winery doesn’t have enough space”, les guys spent last week breaking bottles of old, unsold Haut-Rian that had gone off and were taking up valuable space. Pauline had looked into whether it could be donated, but even in France, homeless shelters and food pantries don’t want old wine. Breaking a couple thousand bottles one-by-one was unfortunately the best solution that could be come up with. Meanwhile, the field work has started up again, with the installation of new wood and iron pickets. It’s very slow work and plentiful due to the havoc wreaked by the picking machine (or the reckless driving thereof, but I won’t name names). Like any endeavor, saving time and labor in one area only creates more in another.

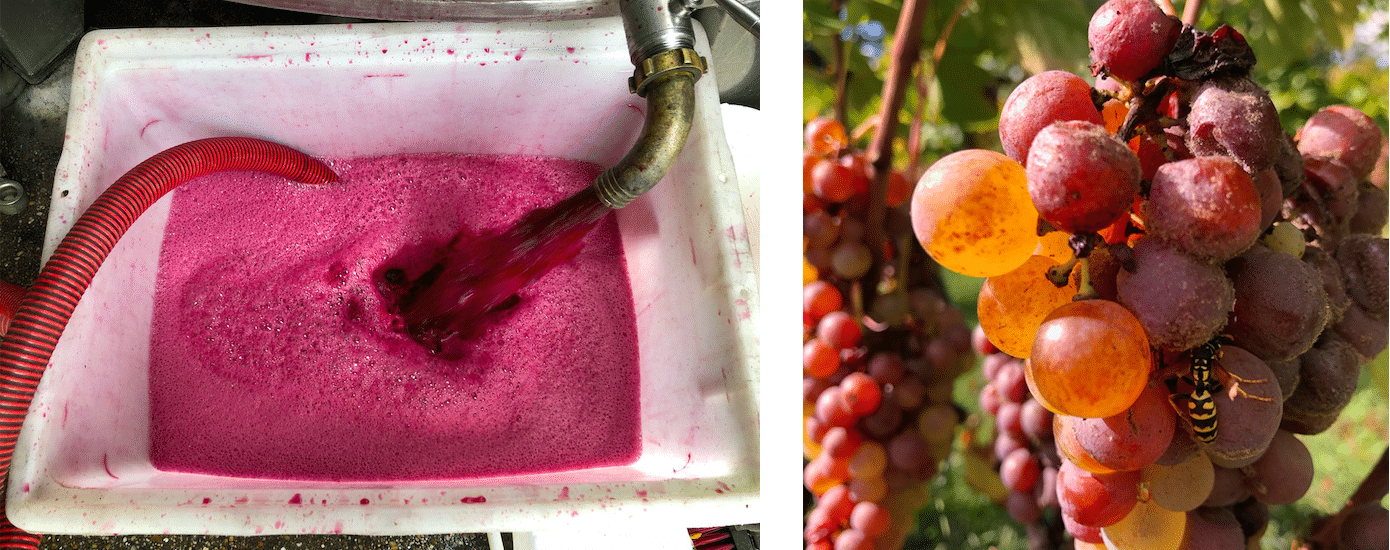

Right now, the main tasks are soutirage (filtering) for the reds and collage (fining) for the whites and rosé. For soutirage, we use gravity to filter out the fine lees (the same way it’s been done for a couple hundred years) by setting up a hose at the top of what is essentially a wine-slide precariously set on top of a ladder, an A-frame scrap of metal, and a big basin. The wine slides down into the basin and is then sucked up by two other hoses and enters a different tank. Once we reach the fine lees, they are sent to another tank from which they will be collected for distillation. For collage, we use pea proteins that we circulate through the tank; they do a much better job than egg whites.

A few weeks ago, a former employee of the winery was visiting and les guys took one look at my stained pants and said, “this is Chloe. She works in the chai.”

A few weeks ago, we celebrated the 110th anniversary of the Cercle Populaire de Rions. Cercles are associative bars unique to Gascogne and were originally seen as a way to bring the Republic into your village (sans women and artists, who were not accepted until 2000 and minus talk of politics). Associative bars are also a way to offer alcohol and food at super low prices. I live literally on the other side of the wall from the Cercle in Rions and on a Friday night it is the spot to hang out (and for those wondering, there are, like, 3 places in town to choose from).

On Friday, we finally celebrated the end of harvest by visiting a local brewery for a tour and beer + cheese tasting, curated by a local cheesemonger. I arrived 3 minutes after the designated gathering time, but was one of the last to arrive. At this point, I am quite comfortable kissing everyone I interact with on the cheek, but there is still something so funny to me about walking into a room and having the festivities literally pause so that you can go around and kiss the cheeks of the 20 other guests. And it’s not only in social settings. Mechanics arrive at the winery and cannot commence their repairs until everyone has been kissed. While at the brewery, we couldn’t help but discuss wine. At a syndicate meeting earlier this week, it was announced that de-alcoholization would be allowed, under strict guidelines (the wine cannot be over 20%, cannot have been chaptalized, etc.). Because of the sun and heat this summer, high sugar levels arrived prior to full organoleptic/phenolic maturity, resulting in a difficult choice for winemakers of when to pick. Pauline recounted the story of being carded for buying a 5kg bag of sugar at the Costco equivalent in Cadillac last summer, in case she was illegally chaptalizing.

Even with some distance, the intensity of harvest is hard to comprehend. It feels like a total blur. But it also truly feels like I made something. As I’ve watched the leaves on the vines turn yellow and drop, I’ve felt so lucky that I got to participate in this annual conversation with nature.”

Chloë Schwartz