Chloë, reporting from Rions – part 3

Our very own Chloë Schwartz left on June 25 for a 6 month internship at Château Haut-Rian, in Entre-Deux-Mers. Read the July 19 and August 16 posts for the beginning of her adventure!

“Hello from Harvest 2019!

It’s sticky and loud. Not just a marathon or a sprint, but a marathon of sprints! As intense as this period is, my days here have never been so rhythmic.

The first day of picking was done by hand. We picked sémillon for a crémant with the team + three helpers (a real French tongue twister trio): Jules, Gilles, and Jean. The rows were so long that it took two hours to get through just one. Besides crémant and vin liquoreux (which will be a mix of late harvest and botrytis grapes), everything is picked by machine.

For those unfamiliar (as I was), the machine sits on top of the vine and goes down the row, pushing the vines through its flaps and shaking off grapes in the process; to me, it most resembles a car wash. However, there’s also a feeling of severity with the machine harvest. We’ve seen many escargots and lizards that have gone through both the picking machine and the destemmer and come out alive but traumatized. One parcel arrived with figs interspersed among the grapes, which I plucked off the conveyor belt and ate.

This is the only time where everybody on the team is working together regularly and, because it’s just us, it definitely brings the group together. Everyone is incredibly nice, ridiculously so when you consider the stress and exhaustion inherent in harvest. It’s a very cooperative, genial work environment; nobody is too good for any sort of task.

What we all seem to do more than anything else is CLEAN. I spend about 6 hours a day cleaning. You would think that the brilliant minds who invented machines to transport, destem, and press juicy, sticky, seeded berries would have designed them with fewer nooks and crannies. If we don’t do a thorough enough job when we clean something like the press, the remaining grape bits will mold and the wine will have faults. It’s a given.

What follows is a description of white/rosé wine production:

My day starts at around 6 a.m. I go to work in the dark, while admiring the stars that are still out. While the first benne (bin) of grapes won’t arrive for a couple of hours, there’s plenty to do beforehand.

There are two presses; one gets cleaned at night and the other in the morning. To clean them, we first remove the pressed skins. They are left in a pile outside to be picked up by a distiller who comes almost daily. Then I suit up in rain gear (boots, jacket, pants) and alternate between power washing and hosing the exterior and interior (with a healthy dose of scrubbing as needed). I climb inside the press while it’s still dark out and emerge to find it has become day and, despite the gear, I’m inevitably colder and wetter than when I arrived.

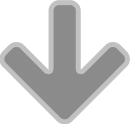

Machine harvest (except for the Crémant and Liquoreux) / gearing up to clean up / early morning tractor fixing.

Other jobs for the morning include: jumpstarting finicky tractors (an ideal task for when it’s pitch black); rinsing any tanks we will be using that day; preparing a big tub of water we rinse our hands in throughout the day (it is dégueu by the afternoon); preparing the cuvon we use as a way-station (the pressed wine lands there before being pumped to its next tank); and measuring the temperature and density of the tanks that have started fermenting (as the sugar becomes alcohol, the density decreases and the temperature increases).

It is encouraged to taste these in-progress tanks. What’s especially cool is that each tank’s fermentation is staggered by approximately 1-2 days, so I have the opportunity to taste the evolution of (e.g.) sauvignon blanc from juice to an almost cider/blonde beer and finally to wine. The initial juice is really delicious and vinous, with depth and nuance. In terms of harvest notes so far, it’s looking like an aromatic vintage for the whites. Pascal told me this is the juiciest year he’s seen on the job, which is surprising because it was such a dry, hot summer.

One morning, Philippe, an oenologue with a lab we use (the menu of analyses that can be done on wine or grapes is truly astounding), came for a visit. He was driven by his sister because, as the oenologue at a few wineries deeper into the Entre-Deux-Mers, he is constantly rushing between jobs and was caught speeding on country roads a few too many times. He had really interesting comments about the developing juice, the earthy vs. mineral nature imparted on the wine depending on the yeast catalyst used, and testing phenolic maturity of red grapes by munching seeds. The seeds should be brown (no longer green) and very nutty, with a bitterness specifically located in the back of the throat. He took a 375mL bottle of Bordeaux Blanc juice with him and left.

When the grapes arrive, we guide the tractor backwards towards the chai, consistently saying “stop” instead of “arrêt” (I find it is easier to say “stop” the way they do, with a French accent). I mark down the time, size of the benne, press being used, and parcel name. On a good day, we can do approximately 8 bennes (approximately 4 hectares picked). When everything is lined up, we unleash the grapes. They travel up a conveyor belt (so that we can pull off any big sticks or other items that may be hard for the destemmer to handle) and then get destemmed and sent to the press. This task requires multiple people: at minimum, someone to open the “back door” of the grape-mobile onto the conveyor belt, someone to fill up wheelbarrows with the discarded stems and dump them once full, someone to manage the speed at which the berries are sent to the press, and at least two people to stand next to the action and chat. If we aren’t vigilant, any of these elements can overflow, which creates unnecessary drama. It is loud and sticky and grape bits are flying everywhere.

After the tractor departs, there’s still work to be done. Throughout the day, we are measuring levels of sugar, total acidity, and SO2 in the pressed juice and samples of grapes that are arriving for maturity tests. SO2 is added to the newly pressed juice. Pressed wine is run through a refrigeration unit. Cold wine undergoes débourbage to get rid of the gross lees (every other day someone comes and filters the juice from the bourbes; Michel says it adds a lot of texture). Yeast is prepared for the commencement of fermentation. Presses are emptied and rinsed (for white wine, we fill the presses completely; for rosé, we leave them partially empty as this results in less color, which is something we are concerned about this year). As an experiment this year, we are separating the free-running rosé juice (the goutte) from the pressed juice.

Another activity was introduced when Géraldine announced, “je vais chercher les fagots dans le discothèque”. Say quoi?? She came back from the building fondly known as the Discotheque with a neatly wrapped bundle of sticks. It turned out it was time to make fagots in their original meaning. They will be used to filter the red wine during délestage. Like so many tasks in the winery, this one is deceptively simple. We trim/clean up sticks and then organize them into tight bundles. On a good day, with two people working, we were only able to produce four. This might also have been because of the intense conversation we found ourselves in (with two more people who weren’t making bundles): why are there so few boulangeries around here and even fewer that are good! This conversation lasted thirty minutes initially and was then brought back up at lunch and the next morning during our coffee/pastry break. This break occurs at 9 or 10a.m. (if we aren’t too busy), when we are only halfway through the morning. The pastries are worst on Mondays when only a few bakeries are open and clearly none of the good ones!

Grapes arriving / color develops in the rosé as the juice is pressed / fagots used to filter the red wine during délestage.

Harvest is an act of juggling; every day, a new ball is thrown into the mix. With that new ball comes myriad things to track, on a timeline different from all the other balls. It is intense. The entire year is riding on this one month and it is easy to slip up. Some mistakes, like thinking a press had been emptied and dumping a ton of grape skins onto the floor which then needed to be shoveled and wheelbarrowed out, are only costly in time and energy. There are decisions to be made at every turn, but it is too early to know exactly how they will affect the final product. All we can do is take detailed notes on our every move. And this is not to mention all of the other regular activities like assembling orders or making deliveries that still happen as though it’s any other time of year.

Around 10:30/11, the only extra person taken on for harvest arrives. Bernard is a local in his 70s with a penchant for capris. A pinch hitter of sorts, his main activities are chatting, eating lunch, and driving the tractor a couple of times. He loves bananas and hates rice.

I am usually sent to eat between 11 and 12. Sometimes the schedule allows us to all eat together, but oftentimes our eating is staggered. Isabelle, Pauline’s mother, makes a delicious, nourishing lunch for us every day of harvest. There is always an appetizer and main course followed by cheese (usually a plate of 3-4 different ones) then fruit then coffee. And wine. And bountiful amounts of bread, which practically replaces the need for a fork, spoon, or napkin. Dishes have ranged from rabbit braised in mushrooms to beef cooked in a corked bottle of red wine (it had no impact on the deliciousness).

After the last benne arrives between 4 and 5, we start cleaning. I have yet to master the act of hosing without getting wet, which is something I’d like to change before it gets too cold. Everyone seems to have a favorite activity in this process; personally, I am quite partial to cleaning the de-stemmer (looks cool, bigger nooks). After the machinery for reception (the conveyor belt, de-stemmer, and juice pump) is cleaned and Pauline has finished cleaning one of the presses, we move everything out of the way. Then one person attaches a jet to one of the hoses used for wine and spray everywhere while everyone else grabs raclettes (squeegees) and pushes the water/juice/berry mixture out of the chai. This activity looks choreographed; it’s the final action of the day and it’s the golden hour, one last burst of energy and camaraderie so we can go home. I am home around 7:15, which is enough time to choose approximately one priority action (dishes, a shower, dinner) and one thing for pleasure before my bed beckons and I get to do the whole thing over again. 6 days a week.

Cleaning of the destemmer, the chai and the press.

That is not to say that there isn’t time for enjoyment! Last weekend, Tallulah (note: Chloë’s sister ) was visiting and we drove to a local castle in disrepair. When we arrived, an older gentleman was hanging out in the doorway with his dog. We walked past him and he said, “what, you think it’s free to enter?” I explained that of course we wanted to pay but did not have the nuance to explain that he looked like just another visitor. Then he asked where I lived and I said Rions, to which he replied that he thought I was going to say Bordeaux because I had a “petit accent”. We are a 45 minute drive from the center of Bordeaux… clearly he does not leave his village often, but I will happily take that compliment.

And what of my massal selection? I narrowed down my sample by 75% and did maturity tests on my top 25 vines. Last week, I went to my parcel as the sun was rising and the fog from the Garonne (the nearby river, a main ingredient in noble rot) crept up through the vines. I picked bunches from the 10 best looking ones (+1 bunch from an adjacent parcel of younger sémillon whose clone is known, to act as a control) and we hosted a tasting over the course of the day. Number of seeds, skin texture, grapefruitiness vs. general citrus notes (Pauline was interested in this aspect because she has always found the parcel to be quite grapefruity), bitterness, and overall favorite were all requested. Unfortunately, I do not think I will have time to thoroughly analyze the data until the vendange is over, but I look forward to it.

Last Friday, I was asked to do a favor for a winemaking couple next door to us. They had forgotten about the tour that comes every Saturday and had plans to be away for the weekend. Yes, during harvest. So I led a tour of their winery on Saturday for a group of English speakers and checked the temperature of their in-progress juice. Despite the proximity, their soil had some major differences: there were oyster fossils in one area, left behind from when this region was under water 35 million years ago, and iron in another because it had once been a Roman iron mine. Pretty cool. Later that day, my landlord knocked on my door and asked if I wanted to come see his hundred-year-old press in action (which is on the floor beneath mine). Duh. Between those two and a little time at Haut-Rian, I ended up at 3 different wineries in one day, all without leaving Rions!

Start of the day at Haut-Rian, and tasting for the massal selection project.

One final note – Isabelle and Michel celebrated their 36th wedding anniversary last week. Knowing they came from winemaking families (in Champagne and Alsace, respectively), I asked about the timing of their wedding with regard to harvest. Isabelle sighed and said that when they got married, harvest never started before October. Now it’s already well underway. A one month shift in a third of a century. Scary.”

Chloë Schwartz