“The 100-mile drive from Les Riceys to Pouilly-Sur-Loire is one of the most beautiful in France, over the rolling farmland of the Morvan. It follows the Kimmeridgian belt and in fact goes right through Chablis (we waved as we drove past Jean-Pierre Grossot). The terroir connection of these wines, Côte des Bar – Chablis – Pouilly-Fumé, is evident. Terroir trumps variety.

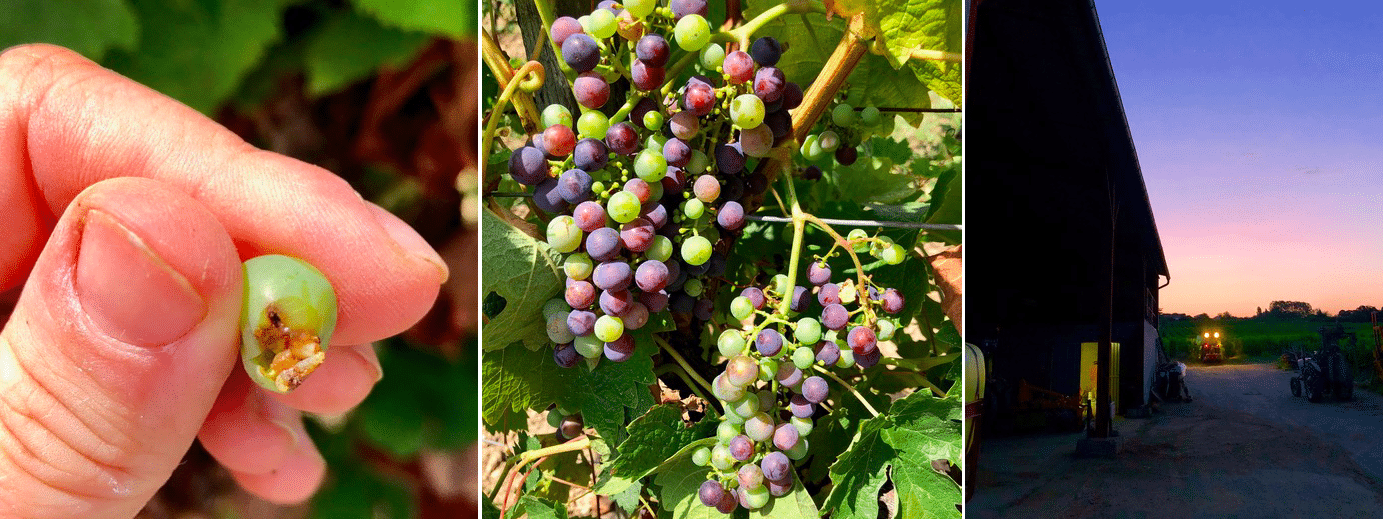

Covering a wide range of a region really informs a lot as to trends and challenges. One thing we saw on this trip from Champagne through the Loire is the fungus known as Esca. The fungus gets inside of a root and kills it. Besides a labor intensive “root canal” the only other solution is pulling out the entire root and replanting—a heartbreak when you have a beautiful old vine. Esca is particularly prevalent among Sauvignon Blanc so it is a bigger problem in the eastern Loire. Another recent issue is due to global climate change. Vineyards that were never frost prone are now getting damaged by late-season freezes. Windmills can be a solution though they are very expensive and not mobile. A positive trend is the move towards larger barrels, especially the 400 liter size. This allows the wine to be less oak-impacted than smaller barriques but still benefit from barrel-aging.

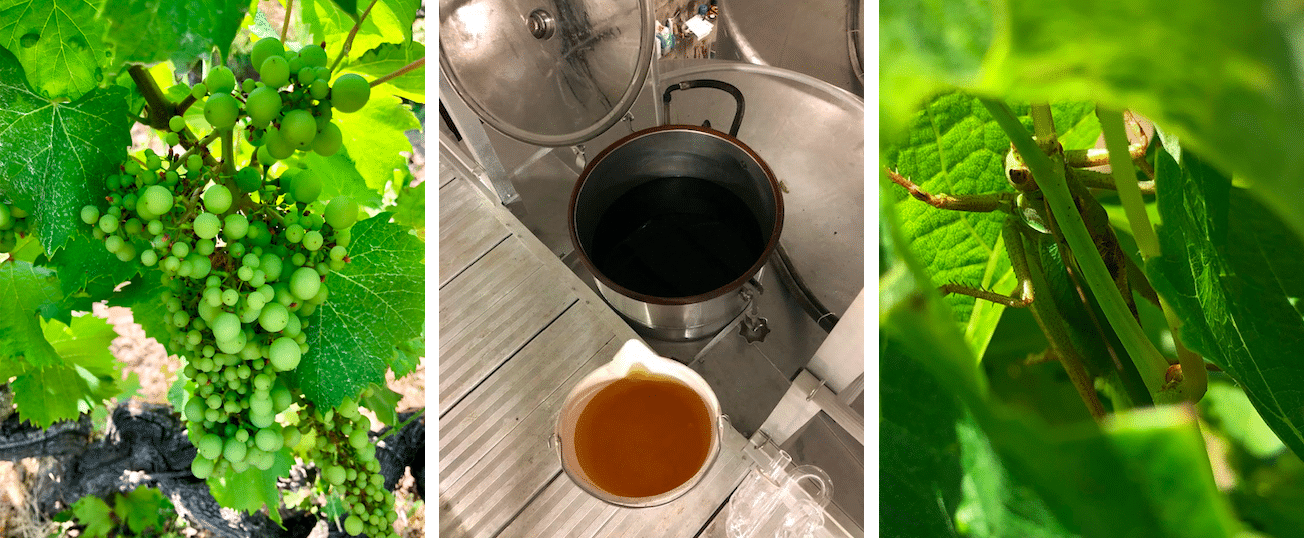

Alain Pabiot, son of Jean, calls his estate Domaine des Fines Caillottes to distinguish themselves from all the other Pabiot cousins in town making wine. Pouilly-Sur-Loire is a wine town and nothing but; there isn’t even a café. It is surrounded by the vineyards that flank the Loire River and contain four distinct types of limestone: Bavois, Kimmeridgian, Villiers and Caillottes. These vineyards lie almost directly across the Loire from Sancerre but the wines have a very different character due to the differences in exposure and soil. We arrived just before the flowering, which was consistent across our entire trip. The vignerons were a bit on edge because along with the imminent expectation of flowers, there was also the expectation of some rough weather, which could hurt the crop before it even has a chance. Floraison is one of the very critical periods in a vineyard.

Alain’s son Jérôme is becoming an important factor in the operation, so we were glad to have him along on our vineyard tour. They don’t want green, vegetal wines, so they work hard in the vineyard to achieve balanced ripeness through leaf-pulling and shoot-training. Depending on what the vintage brings them, they may pull leaves on one side of the plant to bring in more sunshine or the opposite side to reduce exposure and slow down ripening. The latest challenge brought about by climate change is severe frost damage in parcels that have traditionally never been affected. To counter this they have bought seven wind machines (made in Seattle) at $55,000 a pop. They are very effective with each machine covering around 5 hectares. They avoid frost in two ways: drying the grapes and bringing warmer air down to the level of the fruit. They kick in automatically at 35 degrees.

In their very tidy cellar, dug under a number of houses in town, we started by tasting a 2017 Pouilly-Sur-Loire made of 100% Chasselas. The vines are 100 years old and the wine was fruity and charming with a vein of minerality running through its center. Delightful.

We crossed over the river in a northwesterly direction to head to the hamlet of Bué in the appellation of Sancerre. Sancerre gets knocked, or lauded, for its diversity of soil types. Certainly from a commercial perspective, they are the big players in the area and everyone wants to knock them back a few notches. There are 300 vignerons in Sancerre with 150 putting wine into bottle. Picard is one of my oldest suppliers so the welcome is always warm. Young Mickaël Picard now runs the domaine, but I started 28 years ago with his father Jean-Paul, still extremely fit as he climbed their cherry tree to grab handfuls for our guests. He is always light-hearted with a constant smile. Noëlle, Jean-Paul’s wife, has run things at the winery as well as been involved in local politics. She has been the mayor of Bué for the past 10 years. Noëlle is the backbone of the operation.

The difference between Jean-Paul and Mickaël represents the difference in generations of winemakers, father being mostly self-taught, the son more broadly schooled, trained and traveled. Mickaël brings a serious rigor to his work, combined with a deep connection to his terroir. He uses indigenous yeasts for his wines, which he explains makes the wine take longer to develop.

We immediately drove over to the Loire River where Captain Sylvain and his dog Nale greeted us on the boat he built by hand. The entire Picard family were our wonderful hosts and led us through a tasting of their wines. Mickaël bought and planted vines in Menetou Salon a number of years ago so we started with a very fresh 2017 Menetou Salon Blanc. Mickaël uses the same clone of Sauvignon Blanc in Menetou as he does in Sancerre. Due to the fact that these were rather young vines the wine was very direct and simply tasty.

Next was his flagship wine, 2017 Sancerre Blanc. From 40 year old vines, this Sauvignon Blanc had all the depth and complexity that the Menetou lacked. A classic rendition of Sancerre from great vineyards.

The Sancerre Blanc Prestige 2016 is from 60 year old vines in the Chêne Marchand and Grand Chemarin vineyards, 80% in stainless steel, 20% in 400 litre barrels (we saw a lot of this size barrel in the Loire). The oak is from the Loire region. The wine goes through macération pelliculaire (skin contact) before fermentation and rests for at least 6 months in bottle before release. A bigger, deeper wine than the normale bottling, showing some spice from the oak and more complex flavors. This wine would benefit from a few more months to relax and harmonize. (The 2015 we have in stock is singing right now). An incredible value for a white wine of this age and complexity. Just 350 cases/year produced.

35% of Picard’s vineyard is Pinot Noir from which he makes Rosé and Rouge. The 2017 Rosé exhibits fresh, penetrating raspberry flavors. The grapes macerate in the press for 8-15 hours, leaving some stems in the mix. In general, his Sancerre Rosé is made from his younger vines of Pinot Noir.

The 2016 Menetou Salon Rouge from 15-20 year old vines was a mouthful of delightful cassis fruit. Fresh and bright, all in stainless steel. This came from a parcel that the old folks said had once produced great fruit, so they re-planted it and this is the result. It is a perfect red wine for a hot day.

The 2016 Sancerre Rouge could not have been more different; more skin tannins show on the palate, with darker deeper fruit. 50% of the juice goes into 4500 Liter foudre (casks). In the future, Mickaël will go to 100% foudre.

The 2015 Sancerre Rouge – Charlaux grabbed everyone’s attention. He only makes 1500 bottles of this wine which he raises in neutral oak barrels. It is a big wine for this region but perfectly balanced, great length.

Back at the winery Mickaël generously opened some older bottles including a 2006 Sancerre Blanc which still showed terrific acidity holding together ripe, pear fruit. A rich wine that has aged beautifully.

ISABELLE & PIERRE CLÉMENT/ CHATENOY

This winery is going through a necessary name transition to the family name, Clément, from the old Domaine de Châtenoy, but at this point both names are seen throughout the winery. That is a small change for a family that has been making wine here for 16 generations.

After a warm greeting from their gorgeous dogs, Gypsy and Lilly, we headed to the cellars. In fact, the domaine is more of a compound where the Clément family lives and works in numerous buildings. Clément is the major vineyard holder in the small AOC of Menetou Salon and as such, he is a fierce and proud defender of the appellation. He has also served as the head of the Comité for the appellation and helped write the restrictive rules that have helped maintain the very high standards of Menetou Salon wines.

The Menetou appellation is defined strictly by a single soil type, Kimmeridgian marl. It is why the appellation has such an odd shape; it fits the exact contours that follow this vein of limestone. Properly tended, a Sauvignon Blanc vine will live 100 years, which is why Clément uses massal selection to replant his vineyard, instead of buying clones from a nursery. He is more confident using his own vine material to maintain the high quality of his vineyard. Menetou Salon is on the border of Continental and Oceanic climates which is ideal for Sauvignon Blanc. Chablis, further to the east and with the same Kimmeridgian soils is full on Continental and is perfect for Chardonnay.

We tasted the same wines we have in stock, so I will not include any notes, however we did also enjoy a 2007 Dame de Châtenoy at an incredible dinner Isabelle prepared for us. This was the second decade-old Sauvignon Blanc we tasted in 24 hours and it was equally superb, showing perfectly evolved white fruits against a backbone of acidity that kept the wine lively. I think we often overlook high quality Sauvignon Blanc as a vin de garde.

DOMAINE DU TREMBLAY

We continued our journey west and a bit south to the contiguous appellations of Quincy and Reuilly. These are tiny regions that are a mouthful to pronounce (Can-see and Ruh-yee). The Tatin family own vineyards in both appellations and make wines under various labels, with all winemaking now firmly in the hands of young Maroussia Tatin (her mom is Polish, hence the very un-French name).

You actually travel over a major fault line as you cross over to Quincy and the soils change. In the tasting room, Maroussia has the different soil types laid out in boxes for you to see and touch. Her dad, Jean, clearly enjoyed lecturing us on the unique geological aspects of Quincy and Reuilly; he used a pointer to emphasize his explanations on a wall map while Maroussia twitched with embarrassment at his pontifications. We all loved it as we dug deeper into the terroir of the Loire.

Quincy is on a plateau of softly rolling hills, while Reuilly has steep hills with some Kimmeridgian veins. Quincy is perfect for Sauvignon Blanc on its sandy/clay soils, while Reuilly is good for Pinot Noir and Pinot Gris. Clay tends to hold water, and humidity is a challenge. The Quincy appellation is old; it started in 1936, Reuilly in 1937. These are older than Sancerre. Quincy is only a total of 300 hectares (740 acres) and Reuilly is 270 hectares.

Maroussia arranged a tasting for us to match various foods with the wines including oysters, cheese and canned fish. It was fascinating and fun.

All their wines are made with indigenous yeasts and the winery is certified Terra Vitis.

Reuilly Pinot Gris Rosé 2017 was our leadoff wine. Reuilly is known for this gris, a lightly colored wine (think of the Antiquum Aurosa) which gets but 4 hours skin contact. This is also the first wine the Tatins harvest. Beautiful aromatics and fruit.

The Reuilly 2017 Sauvignon Blanc was very refined, emphasis on minerality. Perfect with oysters.

The Ballandor 2017 Sauvignon Blanc is from sandy soils and shows pleasant, ripe, direct fruit. The wine could not stand up to the canned mackerel.

Domaine du Tremblay 2017 Quincy was great with oysters, the fruit and acidity was a perfect match for these sweet, saline creatures. The Quincy 2017 Vieilles Vignes was riper and fatter from lees contact, it was perfect with the monkfish conserve, a full-flavored fish.

The barrel-aged Succelus 2014 was a revelation, for how well Quincy Sauvignon Blanc can age and take oak. It was broad and delicious and very popular with the group.

Reuilly 2016 Rouge is 100% Pinot Noir. It is a fresh and delicious style of young Pinot Noir. We drank this with a veal dish Maroussia’s mom prepared for us and it was ideal – Veau à la Tomate: braised veal shanks cooked in Quincy wine with tomatoes, onions and lots of herbs.

We tasted three special cuvées of a Reuilly Rouge called Cuvée du Pe Miniau (pe is for pépé, ie grandfather), the 2017, 2015 and the 2014. These were dense, well-balanced wines which need time to open up. Lots of potential here.

PATRICE COLIN

We headed northwest to our next stop, the Coteaux du Vendômois. Under the best conditions, this was going to be one of the longer drives of the trip—just under two hours. But the sky opened up and the we drove through a series of crazy deluges, so it took forever. I was super excited regardless. I had yet to visit the Vendômois, one of the few Loire appellations I never stepped foot in. And besides the few wines I have tasted, I knew very little about the appellation. What I also did not know was that this was going to be one of the most exciting, memorable visits of the trip.

Patrice is a very unassuming guy, with a sly smile on his lips as if he knows that he is going to surprise you and upend a lot of your preconceived notions. The Vendômois is a really small appellation, 90% of the wine is made by 3 wineries. The co-op produces a lot of wine; however, half of it is Vin de France, so in fact Colin is the largest producer of AOC Coteaux du Vendômois wines. It became an appellation relatively recently, in 2000. The soils are silex (flint). This is ideal for the preferred Chenin Blanc and Pineau d’Aunis varieties, which have been planted here since the Middle Ages according to Colin. Colin came back home after having made wine in Greece, Germany and Anjou. He started with 10HA that his father gave him and built it up to 30HA today. His family has been making wine here since 1735. He has been organic from day 1 and Certified Organic since 1988; he is proud that he can count over 100 different plant species in his vineyard. He works with very old vines and because he employs massal selection his varieties are unique to his vineyard, unlike the Chenin and Pineau d’Aunis plants found in the rest of the Loire. Both the bunches and the berries are smaller than the same varieties found elsewhere.

With a team of just 7 people, he produces 12,000 cases of a number of different cuvées each year. A full third of his production is made up of sparkling wines. Colin considers his approach to winemaking to be Vin Naturel. He uses indigenous yeasts and his wines go through long fermentations. Vinification is in stainless steel and oak barrels depending on the cuvée; the oak is seasoned at least 3 years before it becomes a barrel. He filters but does not fine. His wines are pure and alive, completely clean, unlike many Vin Naturel, and they scream terroir. Each wine brought another shiver of excitement from the group, due to the unexpected nature of these cuvées and their shimmering quality. All of his wines are eminently quaffable, with low alcohols that make them easy to approach. His overall approach is very similar to Ganevat’s, with the same goal of crafting delicious, accessible wines that express their variety and terroir as purely as possible.

Colin acted completely nonplussed by the excitement at the table while the rain poured down outside the open barn door. But that sly smile was always evident; he knew exactly what he was up to.

We started with a Gris 2017 made from Pineau d’Aunis. The juice from this grape is naturally pink, quite rare. The grapes go directly to the press and are fermented dry. It was not a typical rosé; it inhabits a unique space between a white wine and a rosé, with more emphasis on the minerality of this grape as opposed to the fruitiness which is exhibited in his other wines.

The Gris Bodin 2017 woke all of us up. The first vines for this wine were planted in 1920, and the additions were made in 1935 and 1940 (a pretty brave time to be planting vines in France). This Gris is fermented in barrel (highly thought of in Revue des Vin de France) and is much richer than the first Gris and at just 12% alcohol it was incredibly drinkable. Delicious.

Pierre à Feu 2017 is his first Chenin Blanc and comes from two parcels. The name means gun flint and refers to silex, the soils of these vineyards. Lip smacking dry, this wine starts out with white flowers, a flinty minerality leading to a mouthful of fruit. One-month fermentation in 500 liter casks. 12% alcohol.

The Vieilles Vignes 2017 was just a tease because all of it was sold to Japan. It comes from 50 and 95 year old Chenin Blanc vines which make for a wine rich in flavor and texture. 12.5% alcohol. 3-month fermentation in 500 litre casks. Just 600 cases produced.

The 2017 Pente de Coutis is named for a parcel of Chenin Blanc. It is made in a sec tendre style with 5 grams of RS. It was rounder and softer than his other cuvées but was a bit awkward at this point. It clearly needed time to knit together but all the elements were there for a great wine.

The 2015 C is an outlier made from the 1 hectare of Chardonnay on the property. Scott called it Ganevat of the Loire. It has that Jura-like hint of oxidation on the nose, but it all harmonizes in the glass. Completely dry but has a sweet quality at the same time; fascinating. Low acidity. This is the only white to go through malo.

The Perles Grises was the first of three sparkling wines we tasted. It is a non-vintage rosé, a Pét-Nat of Pineau d’Aunis and just 11.3% alcohol, 6 Bar. My notes just say “crazy delicious.” This is his largest production wine, about 2000 cases, and it is terrific. Penetrating red-berry flavors run straight through the wine. It is Vin de France because that AOC allows Colin to do as he pleases.

Les Perles d’Anne-Sophie is named for his daughter. It is 50% Chenin Blanc, 30% Chardonnay and 20% Pineau d’Aunis made by what he calls méthodes ancestrales naturelles. Basically, it is made without any sugar added at any of the stages of winemaking. There are 1-2 grams of RS. The base wine is from the Pente de Coutis vineyard. Complex and brilliant.

Perles Rouges is from yet another grape variety, Gamay, and just 12.5% alcohol. One would not confuse this with a Gamay from Beaujolais, however the intensity of red-berry fruit speaks to the varietal.

Pierre François 2017 is his first-level red, 60% Pineau d’Aunis, 30% Pinot Noir and 10% Cabernet Franc. A really pretty red wine filled with black pepper and red fruit aromas. Incredible, suave texture on the palate.

Les Vignes d’Emilien Colin 2017 is named for Patrice’s great-grandfather. It is made from very old vines Pineau d’Aunis which are harvested last. The vines were planted from 1890 to 1920. Raised in oak barrels. It is rounder and denser than his Pierre François cuvée but gives up the high notes of black pepper. It’s a bolder, richer version of Pineau d’Aunis. 800 cases produced.

Intuition 2016 was the first wine Patrice told us about when we arrived at the winery. He is excited about this wine for good reason. The Pineau d’Aunis vines were all planted in 1890 by his great-great-grandfather. The vineyard is planted very densely and gives excellent ripeness—he never chaptalizes. Just 200 cases produced. This wine is bottled unfiltered. The fermentation and elevage is accomplished in 1/3 amphorae, 2/3 barrels. Fully de-stemmed, long fermentation. Black fruits, touch of licorice, great length. A brilliant wine.

ALAIN ROBERT

Cyril Robert and his sister Catherine Médard met us at their domaine in Vouvray which they inherited from their father, who bought the property in 1978. They are located in Chançay in the Brienne Valley, just a few miles from the Loire River. Here the soils are sandy, a mix of clay and silex. They also have vineyards along the Loire in Noizay where the soils have more limestone; the combination makes for an interesting mix of fruity and mineral wines.

We have only been working with Cyril and Catherine for a year, but we caught them at an interesting evolution of their winery. Catherine returned to her family estate in 2013 after years working for Jacky Blot, and that level of quality is her goal. When the siblings inherited the winery from their father they had a mostly local clientele who preferred easy-drinking, sweet, sparkling wines (Alain was the mayor of Chançay). Cyril has the talent to achieve his goal of top quality Vouvray through an open-minded and even experimental approach. He is clear on his goal and is constantly moving closer to it. In the past 5 years he has doubled the production of serious still wines. He prefers 24-48 hour cold soaks and uses minimal levels of sulfites (unlike many of his neighbors). He harvests by hand to bring the healthiest grapes into his winery. This year (vintage 2017), he made one cuvée without any sulfites. He employed a specific strain of yeast that feeds off the bacteria that others use sulfites to kill.

2017 was an especially challenging vintage because the malo occurred simultaneously with the alcoholic fermentation. This is a dangerous situation that Cyril had to navigate very carefully. He likes to use Burgundy barrels, 228 liters but does not like a big toasty-oak impact on his wines. This year he experimented with a barrel bent with steam, not fire, to avoid all sense of toast. He stirs the lees only when he tops off the barrels or casks. They have an incredible aging cellar in which the temperature is a constant 50 degrees year round.

We started with an Extra Brut with zero dosage, 36 months sur lattes and 4 grams RS. It was a gorgeous aperitif wine with a perfect balance between fruit and acidity. Lovely aromatics, custard. Very harmonious on the palate.

Troglodyte is the name of the bird on the label. The base wine for this sparkling is from 2015, also zero dosage, 6 grams RS. You can appreciate the ripeness of the fruit he starts with to have this kind of RS with zero dosage. Counter-intuitively this wine felt drier than the Extra Brut and a lot more complex. Chenin has terrific acidity so it is tricky to sense the level of RS.

Cyril’s goal with his Empreinte 2017 is to express the freshness and minerality of Chenin. This wine does all of that and more. 1/3 aged in cask, 2/3 in tank. The wine is fresh and immediately delicious; it is all right there. This is especially impressive considering it was bottled only one month prior to our visit. Empreinte means fingerprint, referring to the mark of the winemaker and the mark of the vintage. The 2016 is less effusive, like the vintage, more serious and profound fruit.

The Ammonite 2015 was terrific and it took home a well-deserved prize: Silver Medal at the Vignerons Indépendants. The fruit was very expressive and was well harmonized with the 12 month, 100% oak barrel elevage (25% new). This is the star of their lineup, a wine that shows off their incredible terroir.

LES PIERRES ECRITES

It is very exciting to be at the very beginning of a great project with very talented people. Coralie and Anthony Rassin bought the Flamand Deletang estate in 2015 from the retiring owner. Unlike many couples in the winemaking world, Coralie and Anthony interact as a unified team, working together in all aspects of winemaking and viticulture, as opposed to separate areas of responsibility. This Montlouis estate has fantastic vineyard sites and after a long search in numerous regions, the Rassins were very happy to find this opportunity. They hail from Nantes, downriver, but had been making wine in the Northern Rhône at some venerable estates. Coralie made wines at Jaboulet and Francois Villard and Anthony worked for Pierre Gonon. They are enthused by the potential of Montlouis wines which they feel show more citrus and minerality than Vouvray, just across the river. Their vineyard lies on a patch of land close to the Cher River, with the Loire just to the north.

There are just three villages that comprise Montlouis AOC. The Rassins own 8 hectares in total with 5 in the Montlouis appellation. Most of their vines were planted 40 years ago, so they are excited to have such prime material to work with. That being said, the young Rassins brought a lot of progressive ideas on improving the vineyard, beginning with eliminating chemical treatments. They are also going through the painstaking process of lowering the height of each root so that they can gain height with the palisage, opening up and increasing the fruit wall. This year, as we found throughout our trip, the vines are about 10 days ahead of normal. The Rassins expect to be Certified Organic in 3 years.

In the winery, they use indigenous yeasts and do not fine their wines. They prefer 400 litre barrels. For their sparkling wines they do not add sugar for the tirage, working méthode ancestrale. The sparklers rest sur lattes 10 months.

We tasted an unfinished 2017 Les Pierres en Bulles, sparkling Montlouis that has been en tirage 5 months. It was showing gorgeous fruit even at this young stage.

The Les Pierres en Bulles sparkling rose is Touraine appellation, a blend of Gamay, Côt (Malbec) and Grolleau Noir. 8g dosage. The wine had been disgorged just a week ago but that did not hold back the effusive fruit character of this delightful sparkler. Outstanding. They get rid of the first pressing (too many tannins) and the last pressing (skin impurities) in order to bring out the pure, red-fruit characteristics of this wine.

Petits Boulay is the Rassins’ first still Chenin Blanc, and the 2017 is the first wine they have created from start to finish—they took over in the middle of the 2015 vintage and 2016 was destroyed by frost. They were visibly excited to present us this wine and we were excited to taste it. The philosophy of this wine is to show off the pure character of Chenin Blanc and it succeeds with mouth-filling fruit that is a joy to drink. Just 5% of the wine goes into 400 litre barrels, the rest is in stainless steel. It stopped fermenting naturally at 4g RS; the balance is perfect, so they left it right there.

Empreintes 2017 is their top Chenin and is still aging in barrel, 400 litres. The 2015 was aged in 228-litre barrels and the change in elevage is noticeable and for the better. This wine will be bottled in September and released in November, a Christmas present in New York. There is an incredible core of sweet fruit, some of which will dry as it ages. Just a touch of spice from the oak barrel.

They made just one 400 litre barrel of Empreinte 2016 and I am glad we had a chance to taste it because the notes of peach and citrus were delicious. The wine stopped fermenting at 12g RS. They got the ridiculous yield of 4HL/HA in 2016.

The Empreinte 2015 was at a perfect point right now. Its elegant, pure Chenin flavors show off the minerality and citrus notes that the Rassins feel are the core of their terroir.

We finished with a Moelleux wine, the 2016 Les Vallées. There was botrytis but the wine was more passerillé, showing apricot, orange and candied lemon notes. Very impressive.

The Rassins are enthusiastic and show so much integrity that you can’t help but root for them to succeed, which I have no doubt they will. With only one full vintage under their belt they have already enjoyed a highlight piece in RVF. Not a bad start.

STEPHANE GUION

Stéphane has the good fortune to have inherited some of the best vineyard sites in Bourgueil, all on the coteaux, 100 meters above the river. He is a 5th generation winemaker who returned home in 1994 after making wine in Bordeaux, Champagne and Chinon.

He also inherited the belief in working organically from his parents, so his vineyards have been pristine since 1965. He farms 30 different plots of 8.5 HA in a 2KM radius. Amazingly, he is a one-man-show. Guion only hires help at harvest. He works completely by hand and is committed to natural organic winemaking. Guion has learned a few tricks from working organically this long, like adding orange peels to his bouillie bordelaise treatments to help dry out the leaves. Aside from humidity, the vineyard has also been challenged by esca (Guion says it attacks the most vigorous plants the worst, those 20-30 years old). And he has been affected by the late season frosts: in 2016 he lost 70% of his crop, and 10% in 2017.

Cuvée Domaine Bourgueil is his flagship wine. The 2017 was bottled just 3 weeks before our visit. 30 year old vines. Beautiful, direct fruit aromatics, ripe raspberry/strawberry, ripe tannins. A bit edgy just after bottling but I know this will smooth out.

The 2016 Cuvée Domaine is from a more powerful vintage, showing broader, spicy fruit with a very round finish.

Cuvée Prestige 2017 was tasted out of the cuve, it will be bottled in September. He uses minimal sulfur (just at racking) and lets indigenous yeasts do the work. The alcoholic and malolactic fermentations take place in stainless steel. This cuvée is from the oldest vines, picked mid-October, and goes through a longer maceration. The wine shows more of the character of his vineyards (Maupas, Petit Mont, Grand Mont). A very expressive and complex wine. Guion has stopped using barriques since the 2009 vintage as he feels that it dries out the fruit. This has been a general development in the Loire Valley and helps explain why the wines are so much more fruity and approachable now.

The Cuvée Prestige 2016 has lots of crunchy, delicious fruit. It is deeper and darker than the Cuvée Domaine. Great balance and aging potential (10-20 years).

We tasted a Cuvée Domaine 2015 that was still fresh and going strong, evolving very nicely.

Cuvée Des Deux Monts 2017 is from two great vineyards, Petit Mont and Grand Mont, raised 50% in 400 litre barrels, 50% stainless steel. A fantastic wine with great depth. The 2014 Deux Monts was a bit rounder due to its age, and very powerful. The wine was still tight; it will benefit from much more cellaring.

He makes a small amount of Rosé, his 2017 was just bottled 2 weeks ago. It is super savory and dry; Guion prefers the wine to rest so it is ready to drink when he releases it. The grapes are from the same vineyard as the Cuvée Domaine. 50% of the wine is bled (saignée) from the Cuvée Domaine tank.

2010 Deux Monts had an ebullient nose, just fruit, fruit and more fruit. This was only the wine’s second vintage.

The 2006 Cuvée Prestige had wonderful evolved aromatics but the palate dries out. 100% barrique.

FRÉDERIC MABILEAU

I knew this winery by reputation but never had the pleasure of tasting through them. When I found out that he was looking for a NY importer, I jumped on the opportunity to meet him during this trip. He suggested that we meet him on his Loire boat, a simple affair that his wife Nathalie calls their living room. It is small but has everything you could need including a nice, tidy kitchen.

The spread of smoked salmon, oysters and whole shrimp from Brittany, the local cheeses and butter were all fantastic. It is a good thing that the wines were also first rate.

Mabileau created his own estate in 1991 with 10 hectares of calcareous, hillside vineyards in St Nicolas and Bourgueil, however his family have been winemakers in this region since the 1600s. He has been Organic from the outset and has been certified Biodynamic by Biodyvin for the past 6 years. Biodyvin is a certification only for wine and covers viticulture and winemaking. The domaine now comprises 25 hectares.

We began with his two entry wines, a red and a white he calls Rouillères. Chenin des Rouillères Anjou Blanc 2017 is from young vines planted 10 years ago in an unusual terroir for Chenin Blanc. The wine was freshly fruited, straight ahead, delicious, just 11% alcohol.

Les Rouillères Rouge is his largest production wine. It is labeled St Nicolas de Bourgeuil at just 12% alcohol. The aromatics made me scream, Wow! They just jump from the glass. This wine is impossible not to love with its fresh, round Cab Franc fruit, the wine has no edges. Mabileau calls it “Hyper-Digest.”

The 2015 Cabernet Sauvignon – Anjou Rouge, is probably a wine that could not have been made before global warming allowed this late-ripening grape to fully mature in the Loire. Cabernet Sauvignon has been used for years in the Loire as a blending grape, but to make a pure varietal wine would be very difficult. This was the wine’s first vintage, and therefore a bit of an experiment. It was made by carbonic maceration so the fruit qualities are highlighted in this very round and drinkable wine: low tannins but not a typical wine made by this method. It is not explosively fruity. 8-10 days carbonic maceration before being pressed and then fermented in open vats. It is a bit of a hybrid and it works very well.

Les Racines Bourgueil 2015 is from a clay/gravel vineyard planted by Mabileau’s grandfather in the 1950s, just after the war. The vineyard was created by glacial action with 7 meters of topsoil over chalk. The wine rests 18 months in 600 litre barrels. A very ripe berry nose, penetrating cherry notes, very fine but present tannins. Top-notch Bourgueil.

Les Coutures 2015 St Nicolas de Bourgueil is made from 50 year old vines grown on pure gravel. There is less clay in St Nicolas than Bourgueil. Mabileau likes to keep his wines 6-12 months in bottle before release. Like the Racines, he keeps this wine for 18 months in 600 litre barrels (demi-muid). Mabileau prefers these neutral barrels for the way they bring out the pure fruit of his terroir. This wine was even deeper and more complex than Racines. Perhaps the best St Nicolas I have had the pleasure to taste.

Mabileau explained that biodynamics give earlier ripeness with full fruit maturity and lower alcohols. This sounds like a perfect antidote to the current challenges of global warming.

His Eclipse vineyard in St Nicolas is 100% limestone from which he periodically makes his top, though iconoclastic, wine. Eclipse No 11 2014 is the 11th vintage he has made of this wine since 1996 (the year of a full eclipse here). It rests for two years in 600 litre barrels and was bottled in 2016. Right now the wine is still marked by oak and is a bit disjointed though the fruit is deep and impressive. He feels that it will start drinking well in another two years. Not having any experience with this wine, I have to believe him.

Chenin du Puy 2013 Saumur Blanc is made in the red wine appellation of Puy Notre Dame. 2013 was a difficult year. Clay/limestone soils, 600 litre new oak barrels for 9 months, barrel fermented. Golden color, fruit compote, pear, very round, the small amount of botrytis shows through in a very pleasing way. Rich but balanced acidity.

Chenin du Puy 2014 comes from a vintage with less botrytis than 2013 and appears to be a completely different wine from the 2013 though it was vinified similarly. The 2014 highlights fresh bright fruit that lifts off the palate.

DOMAINE DU VIEUX PRESSOIR

I have been working with Domaine du Vieux Pressoir for many years, but about 3 years ago Bruno Albert sold his domaine. Immediately, the new owner started making some changes, all for the good, from winemaking to packaging. Frédéric Etienne is the current winemaker and he brings a lot of experience to his new post.

Vieux Pressoir has 26 hectares of vineyards in Saumur. Frédéric pointed out that the Jurassic-limestone soils here are unique for the Loire Valley but are found in great vineyards like the Côte de Nuits. He also showed us how to identify Chenin Blanc by the pink veins on the leaves. Frédéric is very definite in his opinions on winemaking, such as the need to harvest by machine in order to pick at the peak of ripeness (he feels too many Loire producers bring in under-ripe fruit). He also prefers cement cuves for red wines for their thermic stability (his reds macerate 3 weeks on their skins). He is also experimenting, trying out 1,000 litre amphorae for the first time, from which he will make special cuvées of a white and a red wine from the 2018 vintage.

They make two sparklers, a white and a rosé. All of the riddling and disgorgement is done off premise and to order, this way the wine can be as fresh as possible for clients.

The Saumur Brut has 7g of dosage. Frédéric harvests this wine late so he does not need to add any sugar for the tirage, though he does add yeast. The wine is always a blend of 70% Chenin Blanc and 30% Chardonnay. It is a soft, fruity style of sparkling.

The Saumur Brut Rosé is 100% Cabernet Franc and this sparkling shows real varietal character. Spicy, complex fruit notes. 8g dosage.

Saumur Blanc Elegance 2017 is all Chenin made in stainless steel. It is a dry wine with a softness that gives a slight impression of sweetness, a “sec tendre”. Frédéric said this will diminish over time and melt into the wine.

The Saumur Blanc 2016 had a drier feel to it with an anise note. In general, Frédéric likes to harvest late for better balance and more interesting flavors.

Puy Notre Dame 2015 is from one of the newest appellations of the Loire, a section of Saumur that became an AOC in 2009. There are only 30 producers. The wines must be Cabernet Franc. The wine is raised in stainless steel and shows pure fruit, perfumed because of the special soils in this appellation. Ripe and fresh with good depth and character.

The sweet Coteaux de Saumur 2015 is a delicious and pure wine, along the lines of a Coteaux du Layon, made from botrytised grapes. Being from this minor appellation, it is a crazy good value. 170g RS. The beautiful ripe fruit aromas mingle with mushroom notes from the botrytis.

Going forward Frédéric would like to reduce the yields in his vineyards, get more concentration in the red wines, become Certified Organic and move to Biodynamic. Exciting times at this winery.

DOMAINE DES FORGES

Savennières is all about the geology and the Branchereau family is fortunate to have some of the absolute greatest vineyard sites in the region. Séverine Branchereau was our patient tour guide as she explained that millennia ago, the Aquitaine Basin (Bordeaux region) slammed into the Paris Basin in the region around the Layon River and pushed up a volcano, giving this area great soils for winegrowing.

We started our multi-vineyard tour in Roche aux Moines, a Savennières vineyard which became an AOC in 2011. It is a 22 HA clos with 9 winemakers. The Branchereaus have a 99 year lease from one of the three owners, the Baron Braincard, because he refuses to ever sell any of this incredible vineyard. By law, this vineyard must be organically farmed. The soils are blue and red schistes and the vineyard is a single slope with a southern exposure. Walking the vineyard you can sense that you are in a very special place on our planet.

We also got to see Moulin du Gué and the world-famous Quarts de Chaume in which they own a tiny 0.86HA of this 42HA vineyard. Séverine mentioned that some growers were petitioning for a new appellation that would allow them to make dry wines from this great vineyard site that now only produces sweet wines.

Back at the winery, we started tasting with a 2016 Anjou Blanc d’Audace. The Chenin spends a year in 400 litre oak barrels. They do a tri in the vineyard to avoid rotten grapes. This is a very big style of Anjou Blanc.

The 2016 Savennières Moulin du Gué is a sandy parcel, the most approachable of their lineup of 3 Savennières. It shows light honey and pear notes. Approachable is a relative term for this appellation as Savennières are always deep and complex. The 2016 was harvested at the beginning of October and was bottled last September 2017. It is fermented and raised in 400 litre barrels (20% new oak) for a year.

The first Savennières harvested is the Clos du Papillon. Séverine said that sometimes they make a demi-sec from this vineyard if the conditions are right. This is a hillside vineyard that does not have a drop of dirt, it is 100% rock. It is vinified similarly to the Moulin du Gué but expresses its terroir differently, showing white flowers, peach and greater length and complexity than the Gué bottling.

There is a move afoot to make the Roche aux Moines vineyard a grand cru (there has been a cru system here since 2010). Right now only Quarts de Chaume is a grand cru. The 2016 Roche aux Moines shows its power immediately on the nose which leads to a palate that is ripe, elegant, long and still very young and tight. An exciting young wine that needs to be decanted, as any of these Savennières would benefit.

We then tasted out of barrel some of their 2017s including:

2017 Moulin du Gué, which was surprisingly more intense and flamboyant than the 2016 (found out that they used Papillon fruit for this cuvée in 2017), great nose even at this young stage. Definitely a wine to look forward to. Gué means ‘to look at something,’ as this vineyard is at the top of a high hill.

The 2017 Roche aux Moines was a tiny production because of the frost, just 100 cases made (70% less than normal). In fact they didn’t make any Papillon, the small amount of fruit they had went into the Gué. The wine is incredibly intense, with spicy, deep fruit.

Séverine brought out a large wheel of Roquefort cheese to enjoy with two amazing sweet wines: a 2015 Quarts de Chaume, which had the most amazingly long finish and many years of age in front of it and an SGN 1997, deep golden in color and an explosive palate of flavors that kept changing and evolving in the glass. Both were incredible on their own and with the cheese. It was a shame we were in such a rush, we could have lingered over this wine and cheese for a long time.

JEAN-MAURICE RAFFAULT

I am always happy to see Rodolphe Raffault, a very old supplier of VOS. I worked with his father Jean-Maurice but there is no comparison in the attention to detail and quality that Rodolphe has brought to the estate. Rodolphe’s family has been making wine in Chinon since 1613. It was Rodolphe’s grandfather that started to focus on quality wine solely. Rodolphe’s father Jean-Maurice expanded and planted new vineyards. He was also one of the first to champion the idea of single-vineyard Chinons.

After a tour of his aging cave along the banks of the Loire in Chinon, we tasted through a range of his wines and visited the incredible Clos de l’Hospice vineyard. Raffault’s wines are vineyard specific and come from a number of top quality sites from around the appellation, each with its own distinct characteristics. Since 2009 Raffault has been dedicated to working organically and will be certified in just a few years as each vineyard comes on line. Raffault employs a horse to do the work on the steeper slopes. He manually harvests his top crus. The grapes are fully destemmed, he makes use of a sorting table to select the best grapes, and the top cuvées use only the free-run juice.

The Chinon Rosé 2017 has a pink, onion skin hue. Plenty of upfront strawberry fruit, perfectly offset by fresh acidity. Strawberry, fraise des bois persisting through the finish. The grapes come from alluvial, chalk soils. Rodolphe says this was a saline vintage, an easy clean vintage to make wines.

Only 3% of the Chinon appellation is white wine. Raffault’s 2017 Chinon Blanc was fresh and delicious with minerality, white flowers, a tiny amount of RS and a note of salinity: just a lovely expression of Chenin Blanc.

2017 Chinon Rouge Les Galuches is what Raffault says they called a Vin de Pâques in olden times, because it was bottled for Easter. Les Galuches is a single parcel of alluvial soils along the Loire. A very easily approachable, fully-fruited style of Chinon. It reminds me of a St Nicolas with a firmer structure binding it together. The wine rests 6 months in 500 litre double barriques.

Clos d’Isoré 2017 was tasted out of barrel. This is one of Raffault’s top vineyards, very old vines and composed of pure chalk. The wine is showing great promise early on.

Clos de l’Hospice 2017 from barrel already wowed all of us with its richness and spice. It will not be racked until bottling in February 2019.

Then we tasted an experiment, an extended barrel aged Chinon called Le Puy Picasses from the 2015 vintage. This is a parcel inside the Picasses vineyard. We tasted this out of barrel and it was a big wine, a bit tannic at this point but packed with fruit. We will see.

Then we tasted a 2015 Picasses out-of-bottle, and it was fabulous. Raffault is the largest land-holder (6 HA) of this renown vineyard of 30 HA and 10 winemakers. The vines are over 40 years old and the soils are friable chalk. The wine has a dense core of cherry fruit with chunky tannins. Delicious now with loads of aging potential.

Clos d’Isoré 2016 comes from what Raffault feels is one of his best vineyards. This 6 HA monopole is unusual for being pure chalk. The wine is broad and powerful, vibrant fruit with fine tannins. 2016 was an atypical year of extremes of water (very little) and temperature (very high). He uses the plant material from this vineyard for massal selection, replanting all of his other vineyards. The vines are 80+ years old.

The 2015 d’Isoré was bottled in 2017. It is more structured than the 2016 and more typical for this vineyard, 2015 being a great but normal vintage. The wine needs time.

Clos de l’Hospice 2016 comes from a unique, 0.96HA vineyard in the middle of the village of Chinon, high above the Loire River. The steeply sloped vineyard was a part of the monastery in Chinon and cared for by the monks 500 years ago, until it was forgotten about until Raffault bought it and revived it from scratch. The vines are still young but the fruit is first rate, ripe and high-toned, cherry/raspberry as compared to the much darker fruits of d’Isoré.

The 2015 Hospice showed more oak than the 2016 but was a bigger wine, with darker fruits and a long persistent finish.

The 2011 Hospice was gorgeous, with mouth-filling cherry fruit. Picking time was critical in 2011 because of all the rain. The fruit in this wine is still clean and fresh.

The 2010 d’Isoré was very powerful and structured.

From there we kept tasting bottles back to a 1986 Picasses that was still lovely, with lots of fruit and acidity. Raffault’s wines can age but there is no question that the wines are better than ever now.”

Victor Schwartz